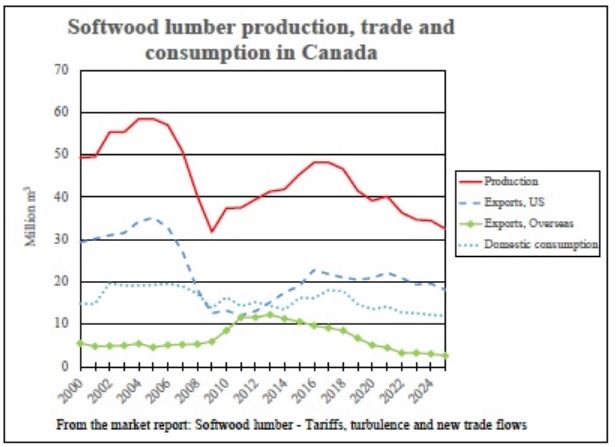

Canada’s lumber industry is heavily export-dependent. Roughly

65% of Canadian lumber production is sold abroad, and the US

remains by far the largest customer, accounting for about 87% of

exports in 2025 (see chart). This reliance leaves Canada highly

exposed to US trade policy.

In 2025, the US imposed new trade barriers on Canadian lumber,

including “Section 232” tariffs and higher Anti-dumping (AD) and

Countervailing Duties (CVD). Combined, these measures increase

Canadian producers’ costs by an estimated 25-30%, significantly

eroding price competitiveness and pushing many sawmills into

negative margins, according to the new market report Softwood

Lumber – Tariffs, Turbulence and New Trade Flows to 2030.

In response, Canada is expected to seek greater market

diversification in regions such as China, Japan, India, Europe,

and the Middle East. However, diversification is challenging.

Canadian lumber is manufactured to North American grades and

sizes, while many overseas markets use different specifications.

Shipping distances are longer, logistics costs are higher, and

building reliable long-term relationships takes time in these

regions.

As of 2025, export volumes to regions beyond the US are near

historic lows (13% of exports in 2025, compared with an average

of ~ 20% over the past 20 years), meaning diversification will

be slow and unlikely to offset reduced US access in the near

term (see chart)

.

Declining log supply is also constraining production,

particularly in British Columbia, which represents a large share

of Canada’s softwood harvest and lumber exports. Over the past

20 years, the province’s allowable annual cut (AAC) has fallen

by one-third due to timberland setasides, Indigenous rights

settlements, insect infestations, and wildfire losses. Harvest

levels have dropped by about half, raising log costs and leaving

many older sawmills uneconomic. This has prompted Canadian firms

to shift investment capital to regions with more abundant and

lowercost timber, particularly the US South.

Because sawmills anchor the broader forest products value chain,

mill closures have cascading impacts. When sawmills shut down,

pulp mills, panel manufacturers, and pellet producers lose

access to residual fiber, which increases their costs and

sometimes forces closures. The resulting contraction affects

employment, rural communities, exports, and GDP.

The Canadian government is responding with financial support and

new procurement initiatives.

Federal measures include loan guarantees to ease liquidity

pressures, funding to encourage product and market innovation,

and “Build Canadian” policies intended to increase domestic wood

use in construction. However, these efforts cannot fully offset

structural disadvantage related to timber supply, high sawlog

costs, and competitiveness in the critical US market, the report

says.

Conclusions

Canada’s lumber and forest sector is expected to continue

contracting through 2030. Sawmill capacity will decline,

particularly among smaller and older operations in regions

affected by insects and fires, and export patterns will slowly

rebalance away from the US. Rural communities will bear the

greatest impacts. If US tariffs are eventually removed, the

surviving modern mills could benefit from improved margins as

lumber prices are likely to increase in the US. Meanwhile,

opportunities exist in gradually growing overseas markets and in

the domestic construction sector, where housing starts would

need to roughly double by 2035 to meet projected demand.

Achieving that, however, would require policy changes,

streamlined permitting, and lower construction costs - none of

which are guaranteed.

Source:

ajot.com