|

Report from

Europe

Certified sustainable business model in Africa

challenged by structural change

A major structural change is underway in the African

timber industry as operations are reoriented away from the

European market towards Asian markets.

This change is driven by factors both on the supply-side,

particularly declining availability of timber species of

interest to the European market; and on the demand-side

as consumption is weakening in Europe at a time when

demand in Asia is rising rapidly.

Although this shift has been going on now for over a

decade, the full implications were laid bare in March this

year with the announcement that the Rougier holding

company was to be placed under court-ordered

receivership proceedings in France with a view to rolling

out extensive restructuring actions.

This event is encouraging a reassessment of the future role

of European forest operations in the African region, and of

the continuing validity of a business model heavily

dependent on the profits anticipated from the sale of third

party certified tropical wood products and other ecosystem

services in ※environmentally-aware§ markets of

richer industrialised nations.

These issues are explored in two recent trade articles, one

by Alain Karsenty1, the Research Director of CIRAD, the

other by Emmanuel Groutel2, an independent expert on the

African timber industry currently affiliated to Caen

University in France. These articles refer respectively to

the ※crises§ and ※brutal weakening§ of European-owned

forest and timber operations in Africa in recent years.

1http://www.willagri.com/2018/06/28/la-crise-de-la-filiere-europeennedu-

bois-tropical-en-afrique-centrale/

2https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323665892_Quid_du_futur_de

s_concessions_forestieres_africaines_dans_le_Bassin_du_Congo

These events raise, in the words of M. Groutel, profound

questions about ※theories of change of all policies and

projects currently underway that rely on the link between

responsible companies and the European and American

market§.

According to M. Karsenty, the bankruptcy filing of

Rougier has come as a particular shock to Europe-based

tropical forestry professionals because the company,

which was founded in Niort in 1923, is ※one of the oldest

and largest timber companies in Africa§ which is present

in Cameroon, Congo and, since 2015, in the Central

African Republic (CAR) and which owned over 2.3

million hectares and employed 3,000 people, mainly in

Africa.

During the on-going restructuring process, Rougier has

disengaged from all African operations, except those in

Gabon. In a transaction concluded on July 16, 2018,

ownership of four Rougier subsidiaries - Soci谷t谷 Foresti豕re

et Industrielle de la Doum谷 (SFID), Cambois and Sud

Participation in Cameroon and Rougier Sangha-Mba谷r谷

(RSM) in the Central African Republic 每 was transferred

to Sodinaf (Soci谷t谷 de distribution nouvelle d'Afrique), a

Cameroonian company.

Financial difficulties of Rougier part of a wider problem

M. Karsenty highlights that the financial difficulties of

Rougier form part of a wider pattern of failure by

European operators in the African tropical wood sector.

The Dutch-owned Wijma Cameroon Group sold four of its

five forest concessions in Cameroon to a competing

company (Vicwood SA, headquartered in Hong Kong) in

2017. The Italian company Cora Wood SA, a well-known

plywood manufacturer operating in Gabon, had to sell one

of its concessions to a Chinese company to pay off its

debts.

M. Karsenty notes that ※rumours are rife about possible

future disposals of other European companies in Gabon or

Congo§.

As M. Karsenty observes, the reasons given by the

Rougier management when filing for bankruptcy this year

refer to problems that are common to the entire tropical

timber export chain in Africa. These include on-going

serious problems and delays with shipping out of Douala

port in Cameroon and delayed payment of VAT refunds

by African governments, partly linked to low oil prices,

which created additional financial challenges for operators

in the region.

While these problems impact on all operators in the

region, they have fallen particularly heavily on Europeanowned

companies because of weak and declining

consumption of tropical timber in the European market;

the declining availability of African wood species that

satisfy the narrow preferences of European buyers; and the

particularly low profitability of certified sustainable timber

operations which receive little or no market premium for

higher operating costs.

Reasons for declining European tropical wood

consumption

The reasons for declining consumption of tropical timbers

in Europe are now well understood, having been widely

reported by ITTO and others. They are also well

articulated by participants at recent trade consultations in

the UK and France hosted by the FLEGT Independent

Market Monitor (IMM), an on-going ITTO project funded

by the EC.

The logistical problems of supplying consistent

commercial timber volumes from Africa into the European

market are compounded by strong EU trends to favour

engineered timber products which in turn require just-intime

delivery of wood in standardised grades and

dimensions which tropical suppliers are not well placed to

provide.

New thermally and chemically modified softwood and

temperate hardwoods, together with wood plastic

composites, are replacing tropical woods in many exterior

applications. African species used in interior applications

每 like wawa, ayous, and movingui 每 are being replaced by

beech, rubberwood, American tulipwood, MDF and a

whole host of non-wood materials.

Meanwhile demand for tropical wood continues to suffer

from the long-term effects of negative media campaigns

linked to deforestation which the certification movement

has not been able entirely to address.

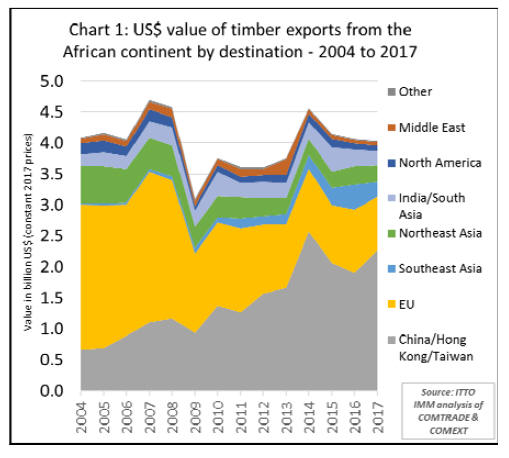

As demand for African timber has weakened in Europe, it

has continued to strengthen in Asia. Trade data analysed

by IMM shows that the share of China in total African

timber exports more than doubled from 25% in 2008 to

57% in 2017. The share of the EU in African exports fell

from 49% to 21% in the same period. (Chart 1).

European African operations transferred to Asian

companies

According to M. Karsenty, ※European dealers, formerly

essential in the African timber industry, are gradually

giving up their assets to Asian investors. Malaysian

operators have been present in Central Africa since the

mid-1990s.

Chinese companies have entered the industry since the

2000s and, more recently, Indian investors, including the

multinational Olam, have made their mark in Gabon and

Congo§.

The process of transferring European-owned industry

assets in Africa to Asian firms has been on-going now for

some time, but there is a feeling that the withdrawal of

Rougier, a company with such long and deep links to

Africa, may mark a turning point.

The share of African timber exports to Europe increased

slightly in 2015 and 2016, due both to a slight uptick in

European consumption and a big fall in exports to China

(mainly due to bursting of the speculative bubble in

rosewood). However, Europe*s share of African exports

slumped again in 2017 and appears to be falling fast in

2018.

The on-going trade dispute between China and the United

States might strengthen these trends. On 2nd August, the

Trump Administration announced a new round of tariffs

on $200 billion in Chinese goods, due to be implemented

from 1st October.

In retaliation, the Chinese government announced that if

the US goes ahead, it will impose a wide-ranging package

of sanctions on imports of US products, including a 25%

tariff on American hardwood.

Such measures are likely to enhance China*s demand for

hardwood products from other regions, including Africa.

And as around 50% of all American hardwood exports are

currently destined for China, it*s also likely to encourage

US hardwood exporters to focus more heavily on the

European market, further increasing competition for

tropical timber.

Declining availability of African timbers of most

interest to European buyers

In addition to these global issues, forestry trends in Africa

are reducing availability of timber species of most interest

to the European market.

M. Karsenty notes that European operators in African have

traditionally focused on a limited range of profitable

species: okoum谷 in Gabon; ayous, sapelli and azob谷 in

Cameroon; sapelli in northern Congo and okoum谷 in

southern Congo; sapelli in CAR; a few precious species

such as wenge and afrormosia in DRC.

Europe*s traditional focus on this handful of species

means that gradually they have become commercially

depleted - although not necessarily endangered.

According to M. Karsenty, ※the problem is economic: the

volumes remaining at the second rotation (legally, 25 to 30

years between two rotations) are generally insufficient to

support industrial utilisation and to satisfy market

demand§.

M. Karsenty notes that this problem is well illustrated by

Rougier which purchased a concession in CAR just over

the border from its main factory in Cameroon as a direct

consequence of the decline in available volumes of sapelli

and ayous in eastern Cameroon, a region that has been

repeatedly exploited (both by industry and small artisanal

operators) for several decades.

Similarly, observes M. Karsenty, Wijma*s abandonment of

several concessions in Cameroon is also linked to the

sharp drop in the volume of azob谷 at the end of the first

rotation. Although there are other species that could be

harvested in these forests during the second and

subsequent rotations, they are either insufficiently

abundant to replace traditional species, or their selling

price is too low to cover the costs of harvesting, transport,

and processing.

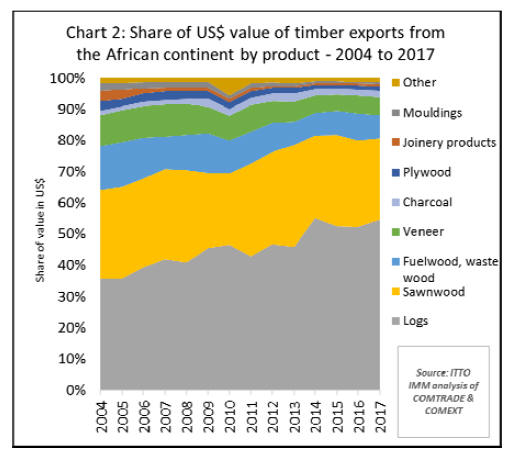

Risk of Africa*s over-dependence on commodities

M. Karsenty also highlights the dangers of African

operators remaining too dependent on exports of

commodities such as logs, standard size lumber and rotary

cut veneers rather than further processed products. He

suggests that ※to sell commodities is to be condemned to

remain a &price taker*, dependent on international timber

prices and the changing preferences of international

buyers§.

Overseas buyers of timber will always tend to focus on the

limited range of species and grades that meet their own

production standards and agendas for market development.

They often have little or no long-term stake in any specific

supply country or region and will turn to alternatives 每 and

play different suppliers off one another 每 when it suits

them.

African suppliers of timber commodities face intense

competition from Asian woods, and increasingly from

modified temperate hardwoods and plantation timbers,

even non-wood products, when prices of African woods

are perceived to be too high.

Some African countries have now placed tight restrictions

on log exports, particularly of the most commercially

valuable species, to boost domestic wood processing.

However, analysis by IMM shows that the rise in African

exports to Asia has been accompanied by an overall shift

away from exports of value-added products at a regionwide

level.

According to IMM, the share of logs in total African

timber exports increased from 41% in 2008 to 55% in

2017. During the same period, the share of higher-value

products such as plywood, joinery products and mouldings

每 which has never been high 每 fell from 5.4% to 2.7%

(Chart 2).

Asian operators better placed than European

operators in Africa

M. Karsenty observes that Asian operators in Africa have

been better able to overcome recent market challenges

than their European counter-parts because they have

significant capital and the markets in which they operate

and can profitably utilise qualities different to those

demanded by European buyers plus they have been

successful in marketing a wide range of species.

Asian companies are under much less market pressure to

demonstrate the legal and sustainable origin of their

products in their domestic markets but this is changing,

especially in China, but Asian exporters have to meet

international standards.

According to M. Karsenty, ※apart from the Olam

company, which bought a large concession already

certified in north Congo in 2011 from a Danish company,

no Asian-owned operator has yet sought to obtain the FSC

label for its African concessions§.

The business model pioneered by European operators for

their African concessions seems to be unravelling. This

model was built on the foundation of forest management

plans developed in the 1990s and extended by a period of

rapid uptake of FSC certification in the period 2005 to

2010.

The success of this model depends heavily on the market

rewards to be derived from a clear commitment to

sustainable forestry and social welfare standards. These

rewards should derive for the combination of greater

market access and prices for timber products, the

anticipated development of new markets for eco-system

services, notably carbon capture, and enhanced confidence

of shareholders and other financial backers.

As M. Karsenty notes, ※while certified woods are sold at a

higher price in some sensitive markets, a good proportion

of labelled timber is sold at current prices in the southern

and eastern markets of Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

And in this case, investment in certification is not

profitable§.

Presentations at the FSC Dialogue meeting held in

conjunction with the Gabon Wood Show in June also

highlighted the continuing failure of this business model to

deliver adequate financial returns. It was noted here that

the total area of FSC certified had declined in the last two

years from 5.5 million hectares to 4.85 million hectares.

The representative of one European-owned FSC certified

operation in Africa said that ※we have reached breakeven

point after several years of negative performance - but

sustainable tropical forest management models are still

economically not attractive enough to motivate traditional

investors to finance new developments.§

This company representative said that while efforts are

being made to monetise carbon credits of certified forest

operations, the returns on this and other ecosystem

services are very low and timber sales still account for

90% of revenue. Furthermore, the large majority of this

derives from their investments in plantation timber which

from a financial perspective (although not from an

environmental perspective) performs better than FSC

certified natural forest.

Too early to dismiss ※certified sustainable§ business

model

While this business model based on certification of natural

forest has been losing ground in Africa over the last

decade - and the problems at Rougier have turned a

spotlight on its viability in the current market environment

- the long-term potential for this model should not be

dismissed out of hand.

To some extent the recent failures of European operations

in Africa are due to economic conditions and policy

failures that may yet be reversed. The timing of the rapid

uptake of FSC certification 每 which occurred just as the

global financial crises began to bite and which had a much

larger effect markets in Europe and the US than in Asia 每

was particularly unfortunate for European operators in

Africa.

The financial crises also distracted policy attention from

efforts to develop markets from eco-system services and

contributed to a general failure on the part of industrialised

nations to back up their environmental commitments with

funds.

More recently there have been some signs of recovery in

total wood consumption in the EU market, buoyed by

rising interest amongst architects and designers of wood*s

environmental credentials.

All imports into the EU are now subject to the EUTR and

while this law does not give FSC and PEFC certified wood

a ※green lane§ through the due diligence requirements, it

does state that certification is an appropriate tool for risk

mitigation.

Both FSC and PEFC have also taken steps to ensure that

their requirements for legal conformance and chain of

custody of standards are fully aligned to EUTR.

Consistent implementation of EUTR, and equivalent laws

in other consuming countries, should eventually give

certified products more of an edge over uncertified

products in these markets.

Progress is slow but prospects for eco-system services are

also improving. Capacity for REDD+ is being gradually

built up, boosted by the strong endorsement of this

approach in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Global carbon markets are also set to expand, notably

following the announcement by China in December last

year that it is launching the world*s largest cap-and-trade

carbon market. This market, expected to be operating by

2020, is likely to allow use of forest carbon offsets,

although the rules for this are still unclear.

The signing of the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction

Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) in October

2016 also promises a significant expansion of demand for

carbon offsets from the aviation industry.

Bolstering market awareness of benefits of sustainable

tropical forestry

More concerted actions are also now being taken by

African operators and certification advocates to bolster

market awareness of the benefits of these systems. FSC

representatives at the Gabon Dialogue particularly

emphasised the work they are doing to raise consumer

awareness of the role of certification in promoting

progress in line with the UN Sustainable Development

Goals.

The message being sent out is that ※certified tropical

timber products come preloaded with rural development

and environmental conservation values§. FSC were

confident that this message is gaining traction, benefitting

from the links to the FSC brand which has gained

widespread consumer recognition in western markets.

Other agencies are now working to promote this message.

With wide-ranging support from major players in the

tropical wood industry, ATIBT launched a new joint

marketing initiative to develop the Fair & Precious brand

in 2017.

Companies that carry the brand are required to sign up to

10 environmental and social values and to demonstrate

progress through commitment to FSC or PEFC

certification.

With support from the Dutch government, the European

Sustainable Tropical Timber Coalition (STTC) is also

raising awareness of the economic, social and

environmental benefits of certified tropical forest

operations. STTC is working to expand the European

market for certified tropical forest products by developing

pan-industry partnerships, promotion of lesser known

tropical species, and provision of technical advice.

This work is beginning to show results. This was

highlighted in a presentation by a representative of SNCF,

the French national rail network, to the Racewood

conference held alongside the Gabon Wood Show in June.

The French railways need more than 12000 m3 of wood

every year. Until recently tropical timbers were not used

because of preconceived ideas about delayed deliveries

and the risk of illegal and unsustainable harvesting.

However, partly encouraged by mounting concerns about

the environmental and health impacts of creosote-coated

softwood alternatives, SNBG have reconsidered their use

of tropical timber. They have developed an action plan to

expand application of certified tropical hardwoods in

collaboration with a wide range of actors 每 including

ATIBT, the French timber association LCB, FSC, PEFC,

and WWF, together with big distributors such as Alstom,

Bombadier, Nestle, Saint Gobain.

SNBG have been particularly encouraged by whole-life

costing exercise which has indicated that, due to the

exceptional technical properties of azobe, when all costs

associated with supply, installation, maintenance, disposal,

and replacement are taken into account, the tropical timber

performs very well against alternatives such as creosote

treated softwood and concrete.

Lower cost certification options

While these initiatives on the demand side are essential to

the long-term future of the certified sustainable tropical

timber business model, the recent experience of European

operators in Africa also highlights the importance of

ensuring the costs of certification do not create an

insurmountable barrier to profitability.

To a significant extent, the certification challenges faced

by operators in Africa are symptomatic of the reliance on

only one international system 每 the FSC 每 and the slow

evolution of regional capacity for certification.

Speaking to the Racewood conference in June, Jean-Paul

Grandjean of PPEFC II, an initiative of COMIFAC to

encourage development of certification capacity in the

Congo region, explained the many measures been taken to

actively support forest operators to maintain their

certificates, through training, building of certification

institutions and networks, and scientific research.

However, M. Grandjean also observed that a specific

barrier to FSC certification in Africa was raised in 2014

with passage of Motion 45 of the FSC General Assembly

on Intact Forest Landscapes (IFL).

This led to greatly tightened FSC requirements for any

forest identified as an IFL, for example that lowimpact/

small scale forest management and non-timber

forest products must be prioritised in unallocated IFL

areas, first access must be provided to local communities,

and alternative models for forest

management/conservation (for example for ecosystem

services) must be developed within IFLs.

While the FSC requirements for IFL may appear desirable

in principle, their implementation would always be

extremely challenging in the business environment

prevailing in the Congo region 每 with only limited returns

to be gained from eco-system services, declining

availability of the most commercially valuable species,

very patchy and highly inconsistent international demand

for certified wood, and lack of institutional capacity to

certify large numbers of community forests.

In the light of these developments, the emergence of a new

certification framework in Africa that is directly

responsive to regional conditions and prioritises regional

institutional capacity is a positive development.

Earlier this year, the first certificate covering an area of

600,000 hectares was awarded by PAFC Gabon, a

certification system endorsed by the international PEFC in

2014 after 5 years of development. The PAFC Gabon

standards are derived from ITTO principles and adapted

specifically to the national context.

A similar PAFC process is also now underway in Congo,

where it is supported by the Ministry of Forest Economy

with financial assistance from the African Development

Bank. A protocol agreement was signed between PAFC

and the international PEFC in 2014, and the PAFC Congo

was formally constituted as an independent agency in

2017.

|